Supporting Dependents during the First World War

When Canadians talk about the First World War, there are common topics we talk about - Vimy Ridge, why people joined the military, the home front, etc.

Today, I want to look at an aspect of the home front that is not as visible and is not spoken about as often. Supporting dependents.

Overall, we have many letters from soldier to their families. Their letters were sent to Canada and could be preserved. But, the letters from wives, mothers, and children to the soldiers are not common. Which makes sense. No matter how much these letters meant to soldiers and Nursing Sisters, they could have limited possessions on them. Soldiers on the front had to carry everything in their pack, and everything would be covered in water, mud, and blood. Not an environment where paper can survive.

When the Great War started, government and economists believed it would be a short war - modern (for the time) military equipment was more decisive and no one's economy could handle a long war. As we know, this was wrong and instead of being over by Christmas, the Great War lasted 53 months.

So instead of having to live off a soldiers salary for a few months, families found themselves without their main breadwinner for years, if he ever returned home. This is where the Separation Allowance and Canadian Patriotic Fund (CPF) came in, but they were not without their many problems.

Marriage before the First World War

If a soldier wanted to get married before the Great War, it was not exactly easy. For example, a Permanent Force (PF) Lieutenant needed permission from the Militia Counsel to marry. The Militia Counsel would need assurance from the Lieutenant's commanding officer that the Lieutenant had the means to maintain himself and a family "in a manner befitting his position as an officer." Other ranks needed to persuade their commanding officer that, not only did he have the means to support himself and a family, but that the woman was of desirable character - something not asked of a Lieutenant's possible wife as they were "presumed to be a lady and above such questions."

The benefit of having this permission to marry was access to free married quarters or a subsistence allowance. Men who married without permission could be compelled to live in the barracks and receive no subsistence allowance.

Between 1914 and 1919, about 619,586 Canadian men and women joined the CEF. While only 1 in 5 left behind a wife and children, many of these soldiers were the sole/main supporter for their parents or other family member. After the war, close to 20,000 widows, mothers, or other dependents received "pensions designed to keep them in respectable poverty until their death or until someone else could be persuaded to provide for them."

Soldier's Wages

To Colonel Sam Hughes', minister of militia under Sir Robert Borden's Conservative government, credit, one of the reasons they prioritized certain soldiers as they did when recruiting for the War (unmarried men, then married men with no children, and actively discouraged married men with children) was because Colonel Hughes knew their wives would be unable to support themselves and their children on a soldiers pay. This is also why married men needed the permission of their wife before they could go to war.

So what were these soldiers paid?

In 1914, a Canadian manual labour worker needed to make about $2 per day to support their family (themselves, wife, and children). Keep in mind, in 1914, men strove to make enough so their wife could be a stay-at-home wife and mother rather than out working themselves.

In 1914, before the war started, a Permanent Force (PF) Private made $0.70 per day. Even a Sergeant only made $1.25 per day. However, unmarried men lived in the barracks and their uniform was provided. Married men had access to couples housing or a subsistence allowance. So some expenses were covered.

On August 27, 1914, Colonel Hughes announced the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) pay scale. CEF Privates would earn $1 per day with an extra $0.10 per day as a field allowance. Sergeants would make $1.35 per day plus $0.15 per day as a field allowance. With their food, clothing, equipment, and shelter covered, this was not a bad pay for a man with no one to support. But, everyone knew it was not enough for a married man with a family.

How to Support Families

Colonel Hughes received many telegram messages from wives saying their husband had left them destitute or widowed mothers saying their son was their sole provider. There were also messages from women who claimed their husband was approved because he had claimed he was not married or they had a child out of wedlock with a soldier before the war and could not support themselves on the man's wage. The largest category of men released as medically unfit, were married men.

The issue was the Canadian Government could not afford to pay soldiers more, support the wives/families of soldiers, or afford to increase taxes. They were just coming out of a depression. Therefore, helping these families largely fell to charitable groups, such as the Canadian Patriotic Fund (CPF). But, more on them later.

Assigned Pay

What was Assigned Pay? Essentially, it was the soldier's pay cheque. But, in the beginning, there was much confusion about this. Some soldiers had some of it sent home so they had money on hand for things like additional food or alcohol but were also helping to support their family. Some soldiers kept it all for themselves. Others initially thought the Government was fully supporting their families and they did not need the extra money (once they learned this was not the case, they began to send more home).

Colonel Hughes had his lawyers look into this as it appears he believed more soldiers should be sending money home. This was for many reasons, one was to look after their families but soldiers at war had many ways to spend money - liquor and venereal diseases were an issue . . . But, legally, they could not tell soldiers what to do with this money. This did change though. British Army regulations and the sweeping powers of the War Measures Act meant they could start having more authority over how much money a soldier kept. But, families had to be patient.

Poor Paymasters

Dealing with all these documents, understanding the regulations, and having the the accounting skills necessary was not an easy task and many men were learning on the job. Plus, there were many men who had lied about being married, not because they wanted out of their marriage or anything like that, but because they wanted to serve and knew enlisting would be more difficult if they admitted to being married. Additionally, soldiers were often poorly educated or illiterate. These poor paymasters faced a lot of challenges and any mistakes that cost the government money was taken from either the Paymaster's pay or the soldier's pay.

Then, these Paymasters had to figure out pay changes for those who were promoted, discharged, transferred, died, declared missing, deserted, etc. all using paper documents in the middle of a war.

Some of the additional difficulties came from back in Canada. For example, Howard Ferry's mother was demanding her son support her, but it took weeks to find the right Ferry in the 36th Battalion.

Separation Allowance

The Separation Allowance was $20 per month given to the soldier's dependents (wife, child, mother) by the Federal Government.

But who counted as a dependent and could receive the Separation Allowance? Wives and young children were clearly dependent and eligible. However, claims of mothers being dependent were investigated. Investigators looked at if there were other children who could support their mother or if her husband was able to work, then she did not qualify. After a year, the government had to come out with a definition of "wife" as they soon learned that family structures were not simple as they expected:

For the purpose of the provision of separation allowance, "wife" means the woman who was married to the officer or the soldier in question under the laws of the country where the marriage was solemnized and who has not been separated from her husband by a judicial decree or "separation from bed or board" or other similar decree parting her from her husband's home and children, but where a wife so separated is entitled either by the agreement or separation to regular payments from her husband, or by an order or a competent court to alimony, such wife should be entitled to the extent of such payments or alimony, to the separation allowance.

Even then, they then had to acknowledge, that even without a court order, there were times a separated wife was entitled to the Separation Allowance. Family dynamics are not always incredibly simple . . . who knew?

An issue also arose from men who had been married in England who had abandoned their first wife when they came to Canada. As they were still married to another woman, they could not marry the woman they were currently, and sometimes had children, with, in Canada. If they did, it was a serious criminal offence. The British Army decided support would go to the woman the soldier was with when he enlisted if there was proof they had been together for two years and they were not supporting their first wife.

In 1915, both the government and CPF had to examine the idea of male dependents. For example, John Grant had been paralyzed since 1902. He relied on his wife who ran their boarding house in Sault Ste. Marie. The Grants had two children, who, because their mother had always coped, never assigned their Separation Allowance to her. She died on May 22, 1915 leaving her husband destitute. Unfortunately, John Grant died before an order in counsel could be adopted regarding male dependents. As J.W. Borden, the Departments chief accountant commented, "there is no reason for an OIC (order in counsel) now." Disturbing comment.

One was adopted however by January 16, 1916.

The Canadian Patriotic Fund

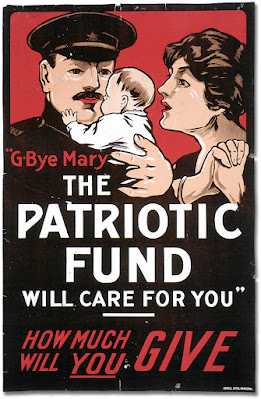

The CPF was a private charity that started during the South African War. For the First World War, they encouraged more men to join by assuring men the CPF would look after their families. A popular slogan was "When some women are giving their men - and when some men are giving their lives - what will you give?"

|

| G-Bye Mary, the Patriotic Fund Will Care for You [Canada], [between 1914 and 1918] Creator unknown Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection Reference Code: C 233-2-5-0-268 Archives of Ontario, I0016186 |

Legitimate challenges for the CPF

The CPF did face some legitimate challenges. For example, the poorest regions had more enlistments and therefore, would require more support. But, they had less money to give compared to the wealthier areas who had more money to give, but lower numbers of enlisted men. The CPF put in national standards where local branches would collect "a reasonable amount of money according to the wealth of the community" and send it to Ottawa. The CPF Treasurer would then send whatever the community needed.

But it was not always a clear system. Women could get money from the CPF based on where they lived, the number of children, etc. This could be up to $25 per month. Plus another $20 from the Government (Separation Allowance). In 1913, the Labour Gazette claimed that an urban family needed $60 per month for food, rent, and utilities, or $45 without a man. This was the minimum.

Over the course of the war, the CPF had to become more frugal. However, they agreed to ignore the Assigned Pay when assessing a families needs to encourage more men to send money home. As a result, some women were better of with their men at war than they were when they were working in Canada. Unfortunately, there were many women who were not better off. For example, one Private left his wife in debt, penniless, and with children to look after. While she believed she was better off without him, she did have children to look after. But, he had changed his name and left for England.

This also did not include the emotional cost and stress places on these families.

Others were not well cared for by the CPF due to classism and racism.

Classism in the CPF

Marriage usually took even working woman from the workforce, even before there were children. So soldiers believed their wives would not need to work with the combination of support they would receive (CPF, Separation Allowance, and Assigned Pay). Within a year, the wives of CPF officials, both branch and executive officials, were concerned about the supply and price of domestic labour. After all, was the CPF supporting women who could be working in their kitchens and laundry rooms? But, the CPF was also aware that the optics of making these women work while their husband's were overseas dying in the war would be horrible.

In the end though, they were essentially saved from making this decision because women were needed in the war effort and working in jobs that use to belong solely to men, plus inflation. So the CPF decided that if a woman did not have a home to look after (AKA had children) and was able to work, she was expected to be working and would receive no more than $5 from the CPF per month.

As the war dragged on, those donating to the CPF wanted reassurance that this money was not being wasted, that women were not better off than they had been when their husbands were home, that these woman were "deserving". Those who were determined to be undeserving could be dropped with no appeal.

Asking for help was difficult for many woman. Many found it humiliating. But, they swallowed their pride for the sake of their family. Only, for many, for the CPF to decide they were undeserving.

What did it mean to be undeserving? For some, it meant they were spending frivolously (according to the CPF inspectors views). Spending frivolously could be buying a child newer clothing when maybe their older ones were fine, spending too much on food, not saving correctly, etc. The CPF were acting as moderators of norms and morals, so anything from (what they viewed as) frivolous spending to adultery were cause for the CPF to stop providing aid.

CPF also played a role in having children removed from homes. Sometimes because the mother was "immoral." The CPF was a charity run by the middle and upper classes. Although branch officials could be sympathetic, there was not always an understanding of how difficult life was for these wives, mothers, children, and other dependents.

Racism in the CPF

Indigenous families were also mistreated by the CPF. Wesley Peters left his mother behind when he joined the First Contingent. His mother, needing help, appealed for aid. The CPF investigator commented, "This man is an Indian, and, evidently, he did not know enough to apply for any allowance for his mother."

Considering the issues that I already covered with figuring out payments and aid, Peters can hardly be blamed for not knowing what was available for his family.

This statement becomes even more ridiculous when you learn that Indigenous families initially could not apply for the CPF! The CPF's argument was that the federal government was already supporting these families. Despite Indigenous communities contributing to the CPF and the CPF actively seeking donations from Indigenous communities, it was 1917 before wives and dependents could receive support. Even then, a close eye was kept on those receiving this support.

Even if you were approved for funding, few received the full amount. The Department of Indian Affairs butted in, claiming "recipients might not be in a position to deal with the full allowances themselves." So, that Department decided how much money was actually sent to families. Only a small fraction actually made its way in the pockets of these soldiers' families, and most was placed in special accounts, overseen by Department of Indian Affairs officials, to be spent later on Indigenous soldier's children to "give them a splendid start in life." This money tended to disappear and the government did not investigate to see if it was bad management or fraud.

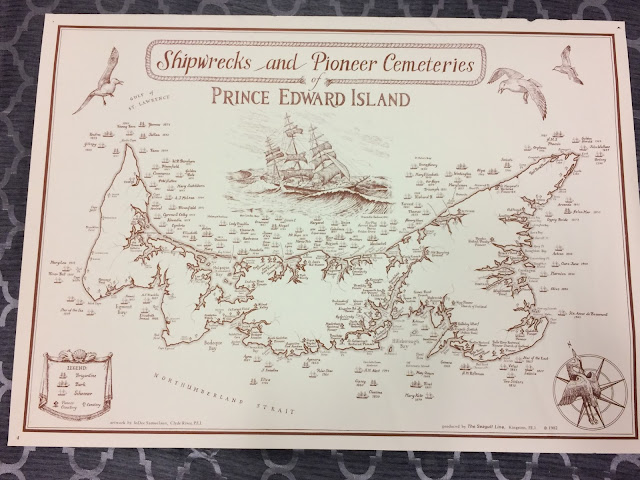

The CPF even had this poster circulated (I could not find the exact date this began circulation) in an attempt to simultaneously encourage Indigenous communities to donate and shame white people into donating:

|

| Canadian Patriotic Fund © IWM (Art.IWM PST 12495) |

According to the Imperial War Museums, the letter says

Onion Lake Indian Reserve, Saskatchewan, Dec. 4th, 1916 Sir Herbert B. Ames, Ottawa Greetings: You asked me to tell you a story about how it came into my mind to pay a little towards 'War Money.' I heard there was a big war going on over there and I feel like I want to help you some way and the best I can do is to send a little money for I can't go myself as I am nearly blind. This is to show you I like to help you. I am an Indian. I heard that other Indians were going to give 25c. each out of their treaty money. I give $1.50 out of money from the Government for beef I sell the agency. I am about 50 years old and my wife and two sons are living with me and my son's wife and her child. That is the way I make up that $1.50 - - 25c. each for six. I shake hands to you, (Sgnd) Moo-che-we-in-es.

The line, "My skin is dark but my heart is white" was designed to both shame white people who were not contributing to the CPF, but also encourage assimilation of Indigenous communities by portraying "white" as a virtue.

The CPF actively sough donations from Indigenous Communities but refused to provide services until 1917. These families and communities deserved better than to be used by the CPF.

CPF Downfall

Although the CPF may have started with good intent, by the end of the war, many provinces did not trust them. Near the end of the war, inflation was rampant, and people could see the discrepancies around them. For example, Sir Joseph Flavelle was a meat-packing baron before the war. However, he became the chair of the Imperial Munitions Board and was adding to his fortune by selling bacon to the army.

Munition workers knew they were making unprecedented amounts working in munition factories. They knew they were making more than soldiers dying overseas and could see the lack of support being given to the wives, children, mothers, and other dependents of these soldiers in their communities.

If CPF decided a dependent was undeserving of support, there was no recourse.

CPF officials and investigators were seen as meddlesome and cruel.

When the Second World War began, the CPF was not reinstituted as the responsibility for soldiers family was seen as the publics responsibility.

Canadian War Museum. "The Canadian Patriotic Fund." Accessed March 9, 2024. https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-home-during-the-war/the-home-front/the-canadian-patriotic-fund/

Cook, Tim. Canadian Encyclopedia. "Canadian Children and the Great War." Accessed March 21, 2024. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-children-and-the-great-war

Duhamel, Karine and McRae, Matthew. "Manitoba History: "Holding Their End Up in Splendid Style": Indigenous People and Canada's First World War." Manitoba Historical Society Archives. Number 82, Fall 2016. Accessed https://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/82/indigenousfirstworldwar.shtml

Morton, Desmond. "Supporting Soldiers' Wives and Families in the Great War: What was Transformed." In A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War, edited by Sarah Glassford and Amy Shaw, 195-218. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012.

Paluszkiewicz-Misiaczek, Magdalena. "“They Should Vanish Into Thin Air ... and Give no Trouble”: Canadian Aboriginal Veteran of World Wars." Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 19, Issue 2: 115-136.

Comments

Post a Comment