Why Were Canadian Boys Fighting in the First World War?

Have you heard the stories of underage boys who enlisted in the First World War in Canada? You may find it hard believe but thousands of underage soldiers are believed to have served for the Canadian forces in the Great War.

How many? Well, Canadian historian Tim Cook estimated that about 20,000 underage boys made it overseas and thousands more are believed to have been turned away at recruitment centres.

Why Serve?

These boys went to war with the same gusto, and misunderstandings, as men.

They wanted to do their bit, make some money, see new places, and be home within a year - remember, when the Great War started countries and citizens thought it would be over in about 6 months to a year.

Many boys who tried to enlist were turned away, the exact numbers are unknown because it wasn't something recorded.

The Tradition

Boys in war is a long standing tradition in numerous countries. Squires in Ancient England, for example, began training at 12 year old for their military roles. Boys also served in military bands, usually as drummers or as bugle players to ensure soldiers knew when to march forward. Britain, and other countries, had boys in their armies and navies long before the Great War.

In fact, underage Canadian boys even enlisted for the Boer War, such as Douglas Williams who was a bugler in Toronto's Queen's Own Rifles. He sailed to Africa when he was only 14 years old. So when Britain declared war on Germany, it wasn't an outlandish thought that boys could serve in some form overseas.

Enlistment

When the Great War started, soldiers had to meet the following criteria:

1. Had to be at least 5 feet 3 inches tall and your chest had to measure a minimum of 33.5 inches - certain positions had different requirements. For example, you had to be at least 5 feet 7 inches with a 34.5 inch chest to be an artillery gunman;

2. Married? You needed written permission from your wife (until August 1915);

3. Pass a medical exam - in the beginning, up to 40% of volunteers were rejected because their eye sight, hearing, teeth, or feet (couldn't have flat feet) failed the exam;

4. And you had to be between the ages of 18 and 45.

Of course, this doesn't mean recruitment officers always followed these guidelines.

As you can imagine, these high standards dropped as the war dragged on and got worse than anyone expected! Even in 1914, people who didn't meet some of these requirements were accepted.

When recruits were signing up, they had to fill in their own birthday and doctors filled in the apparent age in years and months on the health forms. But, no official documents, such as the birth certificate or baptismal record, were required. This made it very easy for some underage boys to get into the official ranks on their own. This was especially true for boys who worked on farms or in trades that required physical labour as they tended to be larger and stronger than boys not doing that type of work. Hence, they looked older and could pass for being over 18.

However, they could enlist (provided they met the other requirements - theoretically) if they had written permission from a parent.

Interestingly, overseas the British age limits for trench warfare stated soldiers had to be at least 19, not 18. Canada, as part of the British empire was supposed to follow these rules. They usually didn't. If the boy was a good soldier, as they usually were as they were eager to prove themselves, they just ignored this regulation.

Russell Mick: A Case Study in Ignoring Criteria

Russell Mick, of Pembroke, Ontario, enlisted at his local recruitment centre on March 17, 1916. Mick claimed he was born on April 4, 1898 which would make him just shy of his 19th birthday (the age limit was 18). On his attestation papers, his apparent age was recorded as 17. Making him underage. Despite this, and rather obvious health issues, the recruitment officer and medical officer signed off on his service in the 224th Forestry Battalion.

About a month later, he was off to England. In England, he was hospitalized and sent back to Canada as unfit to serve due to medical issues. But, Mick was determined to serve and, in the same city, enlisted again on February 20, 1917, less than a year after his first enlistment. This time, his apparent age was recorded as 18, he claimed his birthday was on June 6, 1898, and he noted he had previously served with the 224th Forestry Battalion!

Worried Parents

As the nature of the war became clear, parents became very worried over the situations their underage sons could face. Until the summer of 1915, parents could have their sons pulled from duty and sent home, essentially rescinding their permission for their sons to serve.

However, as recruiting numbers were declining, this right was discontinued after the courts decided that serving was a pact between the army and the recruit, no matter their age.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the harsh realities of the war that were heard about in Canada - many newspapers were realistic about the number of men who were dying and missing, etc. - boys kept enlisting throughout the war.

Black, D and Boileau, J. Old Enough to Fight: Canada's Boy Soldiers in the First World War. Toronto: James Lorimer and Company Ltd., Publishers, 2013.

How many? Well, Canadian historian Tim Cook estimated that about 20,000 underage boys made it overseas and thousands more are believed to have been turned away at recruitment centres.

Why Serve?

These boys went to war with the same gusto, and misunderstandings, as men.

They wanted to do their bit, make some money, see new places, and be home within a year - remember, when the Great War started countries and citizens thought it would be over in about 6 months to a year.

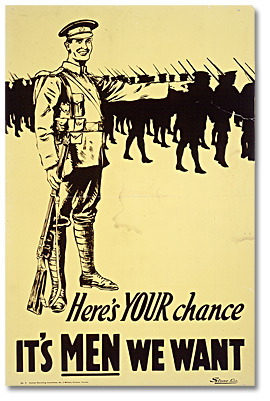

|

| Many boys were eager to prove they were men (Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection, Reference Code: C 233-2-4-0-200, Archives of Ontario, I0016180). |

Many boys who tried to enlist were turned away, the exact numbers are unknown because it wasn't something recorded.

The Tradition

Boys in war is a long standing tradition in numerous countries. Squires in Ancient England, for example, began training at 12 year old for their military roles. Boys also served in military bands, usually as drummers or as bugle players to ensure soldiers knew when to march forward. Britain, and other countries, had boys in their armies and navies long before the Great War.

In fact, underage Canadian boys even enlisted for the Boer War, such as Douglas Williams who was a bugler in Toronto's Queen's Own Rifles. He sailed to Africa when he was only 14 years old. So when Britain declared war on Germany, it wasn't an outlandish thought that boys could serve in some form overseas.

Enlistment

When the Great War started, soldiers had to meet the following criteria:

1. Had to be at least 5 feet 3 inches tall and your chest had to measure a minimum of 33.5 inches - certain positions had different requirements. For example, you had to be at least 5 feet 7 inches with a 34.5 inch chest to be an artillery gunman;

2. Married? You needed written permission from your wife (until August 1915);

3. Pass a medical exam - in the beginning, up to 40% of volunteers were rejected because their eye sight, hearing, teeth, or feet (couldn't have flat feet) failed the exam;

4. And you had to be between the ages of 18 and 45.

Of course, this doesn't mean recruitment officers always followed these guidelines.

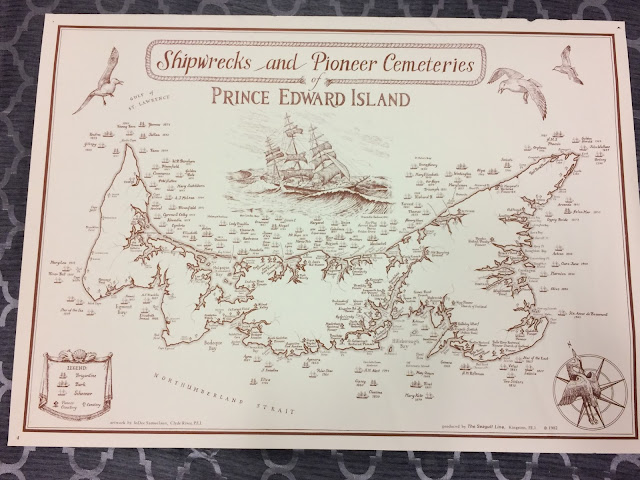

|

| Help the Boys (Canadian War Museum) |

As you can imagine, these high standards dropped as the war dragged on and got worse than anyone expected! Even in 1914, people who didn't meet some of these requirements were accepted.

When recruits were signing up, they had to fill in their own birthday and doctors filled in the apparent age in years and months on the health forms. But, no official documents, such as the birth certificate or baptismal record, were required. This made it very easy for some underage boys to get into the official ranks on their own. This was especially true for boys who worked on farms or in trades that required physical labour as they tended to be larger and stronger than boys not doing that type of work. Hence, they looked older and could pass for being over 18.

However, they could enlist (provided they met the other requirements - theoretically) if they had written permission from a parent.

Interestingly, overseas the British age limits for trench warfare stated soldiers had to be at least 19, not 18. Canada, as part of the British empire was supposed to follow these rules. They usually didn't. If the boy was a good soldier, as they usually were as they were eager to prove themselves, they just ignored this regulation.

Russell Mick: A Case Study in Ignoring Criteria

Russell Mick, of Pembroke, Ontario, enlisted at his local recruitment centre on March 17, 1916. Mick claimed he was born on April 4, 1898 which would make him just shy of his 19th birthday (the age limit was 18). On his attestation papers, his apparent age was recorded as 17. Making him underage. Despite this, and rather obvious health issues, the recruitment officer and medical officer signed off on his service in the 224th Forestry Battalion.

About a month later, he was off to England. In England, he was hospitalized and sent back to Canada as unfit to serve due to medical issues. But, Mick was determined to serve and, in the same city, enlisted again on February 20, 1917, less than a year after his first enlistment. This time, his apparent age was recorded as 18, he claimed his birthday was on June 6, 1898, and he noted he had previously served with the 224th Forestry Battalion!

Worried Parents

As the nature of the war became clear, parents became very worried over the situations their underage sons could face. Until the summer of 1915, parents could have their sons pulled from duty and sent home, essentially rescinding their permission for their sons to serve.

However, as recruiting numbers were declining, this right was discontinued after the courts decided that serving was a pact between the army and the recruit, no matter their age.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the harsh realities of the war that were heard about in Canada - many newspapers were realistic about the number of men who were dying and missing, etc. - boys kept enlisting throughout the war.

|

| "A Canadian Cemetery" (Canadian War Museum) |

Black, D and Boileau, J. Old Enough to Fight: Canada's Boy Soldiers in the First World War. Toronto: James Lorimer and Company Ltd., Publishers, 2013.

canlı sex hattı

ReplyDeleteheets

https://cfimi.com/

salt likit

salt likit

YVJHUN