The First Recorded Murder of a Black Man on PEI

As I have discussed in a previous post, there were slaves on PEI. You can read more about that in my The History of Slavery on PEI post. We do not know much about the lives of these slaves. The main resource on this topic is Jim Hornby's book Black Islanders. So today, I thought we would look at the first, recorded, murder of a black man on PEI.

Not much is known about the life of Thomas Williams. In 1785, he was the property of John Clark. That year, he seems to have participated in a street fight, siding with his friend Jupiter Wise. After this incident, Clark appears to have sold him to George Hardy of Lot 13.

On March 31, 1787, Williams was murdered. Beaten to death.

On May 12, 1789, the Executive Council granted Sheriff James Woodside's request to take Hardy into custody to question him regarding Williams' death. The claim was that "being moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil..." he "with force and arms..." assaulted "a certain Negro-man called Thomas Williams." The indictment stated that Hardy murdered Williams by beating the right side of his head with a stick, strangling him, and beating him with his hands and feet. Attorney-General Phillip Callbeck signed the indictment.

I think it is significant in that a man, Hardy, could be punished for murdering a slave. But, don't think PEI was oh so progressive at the time. Slavery was still legal and Hardy claimed Williams attacked him and he acted in self-defense. I am sure that sounds familiar for people who keep up to date with the news.

As far as the courts were concerned, Hardy's claim couldn't be disproven. He was released and moved to Lot 6.

But, local stories live on. According to Guardian columnist Neil A. Matheson, a story known by some of the older residents of the Bideford area was that Hardy had an "employee", who they believed was either a runaway slave or employee, and they went the sand hills that connect to Hog Island to cut the hay. It was cold and the black man with Hardy (Williams) was not dressed properly for the weather and underfed. When he hesitated to work, Hardy "attempted to convince him with a club." The man put up some defense but was killed. The area where he was murdered at became known as "N***** Point" after that. Even the 1935 Department of Fisheries map of the Malpeque Bay oyster beds referred to the area by that name.

There are a few things I find interesting about this event and I will try to go in chronological order.

1. Hardy was actually investigated for murder. As Williams was a slave, I am genuinely surprised that Hardy could have been charged. I couldn't find too much on the treatment of slaves on PEI so I don't know if there was a precedent of slave owners being charged for how they treated their slaves.

2. The wording of the indictment - "seduced by the instigation of the devil" - implies that Hardy didn't truly have control over actions. But, I also know, given the wording of some legal documents from that era that they had an odd way of phrasing things by today's standards. On the other hand, realistically, if Williams had murdered Hardy this indictment likely would have read very, very differently (and the outcome would have been very, very different).

3. When Hardy's claim of self-defense couldn't be disproven he was released. Williams had many injuries and I wasn't able to find out about Hardy's injuries. Or if he even had any. Meaning, from what I can tell, one man was badly injured and dead and the other man was not injured.

4. Hardy moved from Lot 13 to Lot 6. Why did he move? Did his neighbour's consider him a murderer? While the story of the event does not state Williams was a slave, it clearly defines Hardy as a murderer.

I need to publish some blogs with happier topics. . .

Hornby, Jim. Black Islanders: Prince Edward Island's Historical Black Community. Charlottetown: Institute of Island Studies, 1991.

Not much is known about the life of Thomas Williams. In 1785, he was the property of John Clark. That year, he seems to have participated in a street fight, siding with his friend Jupiter Wise. After this incident, Clark appears to have sold him to George Hardy of Lot 13.

On March 31, 1787, Williams was murdered. Beaten to death.

via GIPHY - Seriously though, Get Out is a good movie!

On May 12, 1789, the Executive Council granted Sheriff James Woodside's request to take Hardy into custody to question him regarding Williams' death. The claim was that "being moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil..." he "with force and arms..." assaulted "a certain Negro-man called Thomas Williams." The indictment stated that Hardy murdered Williams by beating the right side of his head with a stick, strangling him, and beating him with his hands and feet. Attorney-General Phillip Callbeck signed the indictment.

As far as the courts were concerned, Hardy's claim couldn't be disproven. He was released and moved to Lot 6.

|

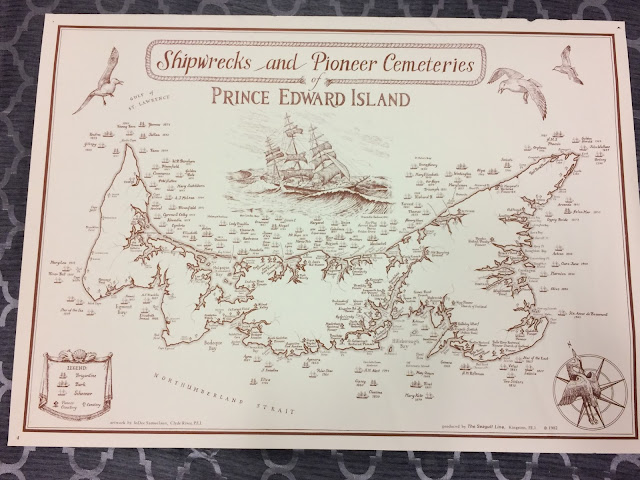

| You can see Lot 13 and Lot 6 on the West end of the Island. Hardy moved from Lot 13 to Lot 6 after the murder of Williams. (Image Credit) |

But, local stories live on. According to Guardian columnist Neil A. Matheson, a story known by some of the older residents of the Bideford area was that Hardy had an "employee", who they believed was either a runaway slave or employee, and they went the sand hills that connect to Hog Island to cut the hay. It was cold and the black man with Hardy (Williams) was not dressed properly for the weather and underfed. When he hesitated to work, Hardy "attempted to convince him with a club." The man put up some defense but was killed. The area where he was murdered at became known as "N***** Point" after that. Even the 1935 Department of Fisheries map of the Malpeque Bay oyster beds referred to the area by that name.

There are a few things I find interesting about this event and I will try to go in chronological order.

1. Hardy was actually investigated for murder. As Williams was a slave, I am genuinely surprised that Hardy could have been charged. I couldn't find too much on the treatment of slaves on PEI so I don't know if there was a precedent of slave owners being charged for how they treated their slaves.

2. The wording of the indictment - "seduced by the instigation of the devil" - implies that Hardy didn't truly have control over actions. But, I also know, given the wording of some legal documents from that era that they had an odd way of phrasing things by today's standards. On the other hand, realistically, if Williams had murdered Hardy this indictment likely would have read very, very differently (and the outcome would have been very, very different).

4. Hardy moved from Lot 13 to Lot 6. Why did he move? Did his neighbour's consider him a murderer? While the story of the event does not state Williams was a slave, it clearly defines Hardy as a murderer.

I need to publish some blogs with happier topics. . .

Hornby, Jim. Black Islanders: Prince Edward Island's Historical Black Community. Charlottetown: Institute of Island Studies, 1991.

Comments

Post a Comment