Remembering a Soldier of Passchendaele: Private Sylvester Militus Lewis

Churches throughout the Island have memorials to soldiers who died in battle or as a result of their wounds sustained in war. St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church has two - Private Fabian J. MacDonald and Private Sylvester Militus Lewis.

Today, we will be looking at Pte. Sylvester Militus Lewis who was killed in Passchendaele in 1917.

Pte. Lewis was born on February 12, 1882, in St. Peter's Bay to Thomas and Catherine (MacInnis) Lewis. He was working in British Columbia as a logger with his cousin when he enlisted on May 1, 1916, in New Westminster, BC. Hence he served in the 29th Battalion, the British Columbia Regiment.

Before enlisting, he was a member of the militia, specifically, the 104th Regiment.

Based on the description of him in his attestation papers, he had brown hair, blue-grey eyes, and was about 5 foot 7 3/4 inches tall with a mole under his left axilla, under his right ear, and on the back of his right leg. When enlisting, distinctive marks are recorded in case the enlistee needed to be identified.

He left Halifax to head overseas on November 1, 1916. When he arrived in Liverpool, he was transferred to the 30th Battalion, which was the British Columbia Reserve Battalion. On January 19, 1917, he was transferred back to the 29th.

In October 1917, the Canadians were called upon to fight in Passchendaele.

Passchendaele

The Battle of Passchendaele was a divisive plan from the start. On one side, you had General Haig, who was in charge of the British forces in Europe (including Britain, Canada, Australia, India, and New Zealand), who wanted to free the coasts and ports of Belgium. On the other side, the Germans were partaking in unrestricted submarine warfare so having more ports was important. But, the French armies were dealing with mutinies and soldiers refusing to fight. It could be detrimental if the Germans attacked French forces.

Haig's solution was to take British soldiers to Passchendaele to capture the plateau that overlooked the area. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was skeptical of this plan and feared it would lead to high casualties with little payoff. But, the British War Cabinet approved of Haig's plan.

Hill 70

Meanwhile, Canada was assigned to attack Lens to draw German attention so they would not attack the French and draw German soldiers away from Passchendaele. Initially, Sir Arthur Currie, who had taken charge of the Canadian Corps in June 1917, had been ordered to launch a frontal attack on the German-occupied and heavily fortified city of Lens. Currie convinced his British superiors that it would be better to attack Hill 70, a large and dominating hill to the north of the city. If it was captured, the Germans would counterattack and the Canadians would have the high ground and Currie believed artillery and machine guns could devastate the Germans and would help to weaken their hold in the area.

The attack started on August 15, 1917, with heavy artillery fire. The Canadian soldiers began advancing towards the enemy on August 21 and soon captured many of their objectives, including Hill 70. They then held those gains against 21 German counterattacks over the next four days.

But this was a hard battle to win. According to Canadian historian Tim Cook, about 10 minutes before the Canadians were set to launch their attack on August 21 at 4:35 am, "the Germans came overland in a bayonet charge behind a heavy artillery and mortar barrage. . . the German frontsoldaten thrust into the Canadian lines, engaging the 29th Battalion in desperate close-quarter fighting, and driving them from their trenches for a few hours." He also describes the 29th Battalion (Pte. Lewis' Battalion) as "fighting for its life."

From what I can tell from Pte. Lewis' service records, he was still serving with the 29th Battalion during this time, which means his Battalion was one of the first groups of Canadians to engage the Germans during this battle.

While the Canadians were victorious at Lens, the same could not be said for the British soldiers in Passchendaele. In September 1917, Haig sent the Australians and New Zealanders to Passchendaele because the British forces were wearing out with high casualties and the condition of the battlefield. These reinforcements did not fare much better. So he called upon the Canadians.

Conditions at Passchendaele

We have all heard Passchendaele was a muddy battlefield. In August 1917, Passchendaele received 127mm of rain, double the average amount for August. September was rather dry, but in October, another 30mm fell in five days. However, the drainage systems in the area were long destroyed by shell fire. The shell holes also provided ample places for the water to sit. New activity in the area, such as shell fire and shifting craters, would sometimes reveal the dead. Sometimes these were soldiers who died recently and others were from previous battles in the area who had been buried in the mud. Some of these craters were deep enough to drown soldiers and horses.

Haig was under political pressure for a victory because Passchendaele was not going well. Desperate for a victory, even if it was symbolic, Haig called upon the Canadians to relieve Australia and New Zealand.

Like other Canadian soldiers, Pte. Lewis went to Passchendaele and fought in these horrible conditions.

Enter the Canadians

Currie did not agree with sending the Canadian soldiers to Passchendaele. Similar to the British Prime Minister, Currie believed the battle would lead to high casualties with few gains. But, he had no choice but to send the soldiers.

When Currie saw the conditions of Passchendaele, he ordered the improvements of gun pits and the improvement or construction of roads and tramlines. Currie wrote:

Aftermath

Currie estimated there would be 16,000 Canadians dead or wounded at Passchendaele.

He is counted among the almost 4,000 who died in Passchendaele.

Pte. Lewis is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial in Belgium on Panel 18 - 28 - 30. The Menin Gate Memorial is located on the eastern side of Ypres in West Flanders and bears the names of almost 55,000 "who were lost without a trace during the defence of the Ypres Salient in the First World War."

Pte. Lewis' name on the Menin Gate indicates that he is one of the thousands whose remains were not recovered from the battlefield.

Sources

Military Service Record of Private Sylvester Militus Lewis.

Cook, T. "Swallowed Up in the Swirling Murk of the Battle." Canadians Fighting the Great War: 1917-1918. 297-307.

St. Peter's Bay Memorial Historical Society, They Chose to Serve. Available at https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://vre2.upei.ca/cap/fedora/repository/cap:1151/OBJ/preview.pdf

"Sylvester Militius Lewis." Canadian Virtual War Memorial. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war-memorial/detail/1593845?Sylvester%20Militius%20Lewis

Roy, R.H. and Foot, R. "Canada and the Battle of Passchendaele." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Published May 31, 2006. Last updated November 21, 2018. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/battle-of-passchendaele

"Passchendaele." Canadian War Museum. https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/battles-and-fighting/land-battles/hill-70/

Tibbitts, C. "Rain and Mud: the Ypres - Passchendaele Offensive. Australian War Memorial. August 1, 2007. https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/rain-mud-the-ypres-passchendaele-offensive

Today, we will be looking at Pte. Sylvester Militus Lewis who was killed in Passchendaele in 1917.

Pte. Lewis was born on February 12, 1882, in St. Peter's Bay to Thomas and Catherine (MacInnis) Lewis. He was working in British Columbia as a logger with his cousin when he enlisted on May 1, 1916, in New Westminster, BC. Hence he served in the 29th Battalion, the British Columbia Regiment.

Before enlisting, he was a member of the militia, specifically, the 104th Regiment.

Based on the description of him in his attestation papers, he had brown hair, blue-grey eyes, and was about 5 foot 7 3/4 inches tall with a mole under his left axilla, under his right ear, and on the back of his right leg. When enlisting, distinctive marks are recorded in case the enlistee needed to be identified.

He left Halifax to head overseas on November 1, 1916. When he arrived in Liverpool, he was transferred to the 30th Battalion, which was the British Columbia Reserve Battalion. On January 19, 1917, he was transferred back to the 29th.

In October 1917, the Canadians were called upon to fight in Passchendaele.

Passchendaele

The Battle of Passchendaele was a divisive plan from the start. On one side, you had General Haig, who was in charge of the British forces in Europe (including Britain, Canada, Australia, India, and New Zealand), who wanted to free the coasts and ports of Belgium. On the other side, the Germans were partaking in unrestricted submarine warfare so having more ports was important. But, the French armies were dealing with mutinies and soldiers refusing to fight. It could be detrimental if the Germans attacked French forces.

Haig's solution was to take British soldiers to Passchendaele to capture the plateau that overlooked the area. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was skeptical of this plan and feared it would lead to high casualties with little payoff. But, the British War Cabinet approved of Haig's plan.

Hill 70

Meanwhile, Canada was assigned to attack Lens to draw German attention so they would not attack the French and draw German soldiers away from Passchendaele. Initially, Sir Arthur Currie, who had taken charge of the Canadian Corps in June 1917, had been ordered to launch a frontal attack on the German-occupied and heavily fortified city of Lens. Currie convinced his British superiors that it would be better to attack Hill 70, a large and dominating hill to the north of the city. If it was captured, the Germans would counterattack and the Canadians would have the high ground and Currie believed artillery and machine guns could devastate the Germans and would help to weaken their hold in the area.

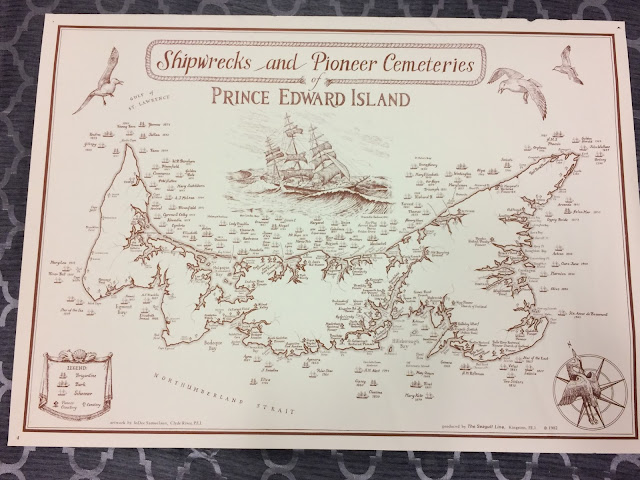

|

| This map shows the locations of both Hill 70 and Passchendaele. As you can see, they are reasonably close to each other, about 65 km according to Google Maps. (Image Credit: The Canadian Encyclopedia) |

The attack started on August 15, 1917, with heavy artillery fire. The Canadian soldiers began advancing towards the enemy on August 21 and soon captured many of their objectives, including Hill 70. They then held those gains against 21 German counterattacks over the next four days.

But this was a hard battle to win. According to Canadian historian Tim Cook, about 10 minutes before the Canadians were set to launch their attack on August 21 at 4:35 am, "the Germans came overland in a bayonet charge behind a heavy artillery and mortar barrage. . . the German frontsoldaten thrust into the Canadian lines, engaging the 29th Battalion in desperate close-quarter fighting, and driving them from their trenches for a few hours." He also describes the 29th Battalion (Pte. Lewis' Battalion) as "fighting for its life."

From what I can tell from Pte. Lewis' service records, he was still serving with the 29th Battalion during this time, which means his Battalion was one of the first groups of Canadians to engage the Germans during this battle.

While the Canadians were victorious at Lens, the same could not be said for the British soldiers in Passchendaele. In September 1917, Haig sent the Australians and New Zealanders to Passchendaele because the British forces were wearing out with high casualties and the condition of the battlefield. These reinforcements did not fare much better. So he called upon the Canadians.

Conditions at Passchendaele

We have all heard Passchendaele was a muddy battlefield. In August 1917, Passchendaele received 127mm of rain, double the average amount for August. September was rather dry, but in October, another 30mm fell in five days. However, the drainage systems in the area were long destroyed by shell fire. The shell holes also provided ample places for the water to sit. New activity in the area, such as shell fire and shifting craters, would sometimes reveal the dead. Sometimes these were soldiers who died recently and others were from previous battles in the area who had been buried in the mud. Some of these craters were deep enough to drown soldiers and horses.

|

| Soldiers transporting a wounded comrade at Passchendaele (Image Credit: The Canadian Encyclopedia) |

Haig was under political pressure for a victory because Passchendaele was not going well. Desperate for a victory, even if it was symbolic, Haig called upon the Canadians to relieve Australia and New Zealand.

Like other Canadian soldiers, Pte. Lewis went to Passchendaele and fought in these horrible conditions.

Enter the Canadians

Currie did not agree with sending the Canadian soldiers to Passchendaele. Similar to the British Prime Minister, Currie believed the battle would lead to high casualties with few gains. But, he had no choice but to send the soldiers.

When Currie saw the conditions of Passchendaele, he ordered the improvements of gun pits and the improvement or construction of roads and tramlines. Currie wrote:

"Battlefield looks bad... no salvaging has been done and very few of the dead buried."On November 6, 1917, the Canadians launched their third attack and were successful at capturing Passchendaele Ridge and the ruins of the Passchendaele village. On the fourth assault, carried out on November 10, the Canadians captured the remaining high areas.

Aftermath

Currie estimated there would be 16,000 Canadians dead or wounded at Passchendaele.

"By mid-November, having captured the ridge, his estimate proved eerily accurate, with 15,654 Canadian fallen."Pte. Sylvester Militus Lewis died at Passchendaele on November 6, 1917, at age 34 in the third attack the Canadians launched.

He is counted among the almost 4,000 who died in Passchendaele.

Pte. Lewis is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial in Belgium on Panel 18 - 28 - 30. The Menin Gate Memorial is located on the eastern side of Ypres in West Flanders and bears the names of almost 55,000 "who were lost without a trace during the defence of the Ypres Salient in the First World War."

|

| Pte. Lewis is listed among the names on the Menin Gate Memorial (Image Credit: Canadian Virtual War Memorial) |

Pte. Lewis' name on the Menin Gate indicates that he is one of the thousands whose remains were not recovered from the battlefield.

"Lost without a trace"Pte. Lewis' sacrifice is also commemorated in his hometown with a stained glass window in the St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church in St. Peter's Bay, PEI.

|

| Stained glass window dedicated to Private Sylvester Militus Lewis, St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church, St. Peter's Bay, PEI (Image Credit: Rita MacKenzie) |

Sources

Military Service Record of Private Sylvester Militus Lewis.

Cook, T. "Swallowed Up in the Swirling Murk of the Battle." Canadians Fighting the Great War: 1917-1918. 297-307.

St. Peter's Bay Memorial Historical Society, They Chose to Serve. Available at https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://vre2.upei.ca/cap/fedora/repository/cap:1151/OBJ/preview.pdf

"Sylvester Militius Lewis." Canadian Virtual War Memorial. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war-memorial/detail/1593845?Sylvester%20Militius%20Lewis

Roy, R.H. and Foot, R. "Canada and the Battle of Passchendaele." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Published May 31, 2006. Last updated November 21, 2018. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/battle-of-passchendaele

"Passchendaele." Canadian War Museum. https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/battles-and-fighting/land-battles/hill-70/

Tibbitts, C. "Rain and Mud: the Ypres - Passchendaele Offensive. Australian War Memorial. August 1, 2007. https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/rain-mud-the-ypres-passchendaele-offensive

Comments

Post a Comment