The West Prince Fire: PEI's Largest Wildfire

As we are in the middle of heat warning here on the Island, it seemed appropriate to cover the West Prince Fire of 1960. As it was an accidental fire and the dryness of the Island (kind of like this past week) were key factors in it spreading to become PEI's largest wildfire!

In August 1960, PEI was experiencing some of its lowest levels of rainfall on the record. We were a "tinderbox waiting for a spark." It was so dry, the grass was turning brown and crops were wilting. In mid-August, there was a fire smouldering for about a week that no one was taking too seriously. But, on August 29, the fire went out of control and would eventually encompass areas between Mount Pleasant and Portage, Port Hill, Foxley River, Springhill, Tyne Valley, Murray Road, Black Banks and Conway!

At times, it was unclear whose homes and farms were being destroyed. But, once this information was known, the newspapers reported it. The newspaper also reported that boats out of Alberton went down the Foxley River after hearing that homes along the river were destroyed and there were people who were unable to leave the area by road. These brave men, Charles and Ray Fraser, Mont Hutt, Bryden Smith, Ron MacKinnion, Myrl Basil, and Silas Mathews, did not find anyone along the shore to rescue.

This fire could also be seen for kilometres around. For example, at the time of this my fire, my Aunt, Betty MacKenzie (McCarthy) was seven years old and living in Brockton on Dock Road, just over 20 kilometres from Portage. She could remember seeing the fire from a hill behind their barn and the night sky being lit up from the fire. As a child, she and her siblings were scared by the fire. I can understand why - falling asleep with the night sky lit up with red must be scary.

But for families like my Aunt's, there was another worry - the cinders. Betty can remember the cinders from the fire being blown around their home and their neighbours. Given how dry it was, those cinders easily could have started another fire! Thankfully, the fire did not extend that far.

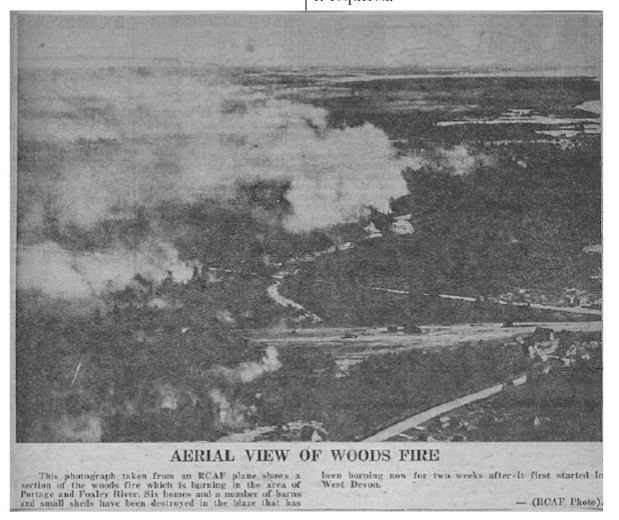

|

| "Aerial View of Woods Fire" (Photo Credit: Thelma Phillips) |

In August 1960, PEI was experiencing some of its lowest levels of rainfall on the record. We were a "tinderbox waiting for a spark." It was so dry, the grass was turning brown and crops were wilting. In mid-August, there was a fire smouldering for about a week that no one was taking too seriously. But, on August 29, the fire went out of control and would eventually encompass areas between Mount Pleasant and Portage, Port Hill, Foxley River, Springhill, Tyne Valley, Murray Road, Black Banks and Conway!

|

| This is a rough map of the area affected by the fire. Made using Google Maps and a photo editor. |

|

| Zoomed out view of where the fires were located. Created using Google Maps and a photo editor. |

The situation only became worse when the wind expanded the fire and five families lost their homes. Like many large fires, the West Prince Fire was the result of many smaller fires, in this case about a dozen, that were burning at the same time near the same area. The sparks from these fires would also cause new fires to start nearby (hence why restrictions are sometimes put on fires). By the time this fire was under control, there were 28 different fires burning in the area.

West Prince quickly mobilized to fight the fires, and they did not do it alone-

- The Royal Canadian Air Force in Summerside provided workers and equipment

- Canadian Army sent reinforcements from Gagetown, NB

- Canadian Red Cross sent disaster services support

- Police and RCMP, at times with army assistance, restricted traffic, blocked roads, and because they did not have two-way radios at the time, drove messages to the front

- The RCMP also helped fight the fires directly

- Community members and people from surrounding communities volunteered to fight the fire

- Volunteers were at the Ellerslie Legion (the efforts HQ) around the clock to provide meals to volunteers, as were the first aid stations.

- Firefighters came from across the Island and Atlantic Canada

- Militia groups, such as the No. 2 Militia Group in Charlottetown supplied equipment

- Donations came from all across the Island

By September 2nd, there were about 500 men fighting the fires over 200 square miles (at the fire's height, there were about 1000 firefighters), 15 tanker trucks, 12 pumps, and countless backpack sprayers. There were also bulldozers working to create fire breaks and 75 dump and transport trucks were available to move people and belongings.

Cigarettes were also made available because, well it was the 60s.

As the fire spread, farmers tried to harvest their crops as quickly as possible, hoping to finish before the fire reached their farms.

Thelma Philips' mother, Vivian, of Freetown, kept a scrapbook of the newspaper articles about the fire. According to Thelma, who transcribed the scrapbook and has made it available on her website, some of the interesting articles she has found include stories of animals being blinded by smoke and heat, the eyes of residents in Charlottetown tearing up from the smoke, a young girl swinging despite the fire burning nearby, and the Premier and his entourage stopping their tour of the area to help save a house on Murray Road.

|

| Home of George Tuplin on Murray Road burning down. When the home caught on fire, the Premier and some of his cabinet were touring the area and stopped to help fight the fire. As you can see, it was, unfortunately, a lost battle. (Image Credit: Thelma Phillips) |

At times, it was unclear whose homes and farms were being destroyed. But, once this information was known, the newspapers reported it. The newspaper also reported that boats out of Alberton went down the Foxley River after hearing that homes along the river were destroyed and there were people who were unable to leave the area by road. These brave men, Charles and Ray Fraser, Mont Hutt, Bryden Smith, Ron MacKinnion, Myrl Basil, and Silas Mathews, did not find anyone along the shore to rescue.

The fire also demonstrated the relationship between the Atlantic Region and Massachusetts - Mrs. Carolyn Emery of Massachusetts called the Summerside Branch of the Red Cross and informed them she planned to collect blankets and other goods through her local Red Cross and have them sent to Summerside to be distributed to those in need.

Preparing for the worst, 10,000 feet of fire hose was flown in from Montreal!

Fighting fires is dangerous. These men suffered smoke inhalation, burns, head injuries, cuts, injuries from falls, and more. There were even reports of the firefighter getting burns and blisters through their heavy boots.

Of course, the police had to warn people to stay away from the area (human are curious beings) and inform them that going to see the fire would only hamper the efforts of those fighting it.

About 12 days into the fire, some had "been heard to say that the main hope for resolving this situation rests in hurricane Donna coming this way." The hope was the heavy rains coming with the hurricane would quell the flames.

The fires finally came under control around September 16, about three weeks later, thanks to the efforts of firefighters and other personnel, three days of rain, and Hurricane Donna.

Once the fires were out, probes started to find out what caused these fires that, combined, created the largest wildfire on PEI.

11 of the 28 fires were blamed on Moonshiners. Forestry officials stated that 11 stills they found were directly responsible for some of the fires. One of the fires was believed to be caused by someone attempting to burn a wasp nest. The origins of the other fires were unknown but some were suspected to be the result of arson. Some of these fire would have also been caused by cinders carried by the wind.

Miraculously, no one seems to have died in the fire.

This fire could also be seen for kilometres around. For example, at the time of this my fire, my Aunt, Betty MacKenzie (McCarthy) was seven years old and living in Brockton on Dock Road, just over 20 kilometres from Portage. She could remember seeing the fire from a hill behind their barn and the night sky being lit up from the fire. As a child, she and her siblings were scared by the fire. I can understand why - falling asleep with the night sky lit up with red must be scary.

But for families like my Aunt's, there was another worry - the cinders. Betty can remember the cinders from the fire being blown around their home and their neighbours. Given how dry it was, those cinders easily could have started another fire! Thankfully, the fire did not extend that far.

So, the moral of the story, whether your moonshining (which is illegal unless licenced), burning a wasp nest, or camping - don't light fires when it's really dry outside.

I want to thank Chris Dennis for suggesting I cover this topic, Betty MacKenzie for telling me about her experience with the fire, and Thelma Phillips whose website provides images and transcribed newspapers from the time.

I want to thank Chris Dennis for suggesting I cover this topic, Betty MacKenzie for telling me about her experience with the fire, and Thelma Phillips whose website provides images and transcribed newspapers from the time.

"Fifty years after forest fire ravaged West Prince, stories now online." The Guardian. September 30, 2017. http://www.theguardian.pe.ca/living/fifty-years-after-forest-fire-ravaged-west-prince-stories-now-online-108963/

Phillips, Thelma. "West Prince Fire." http://www.thelmaphillips.ca/styled/index.html

Kensington. https://kensington.ca/wp-content/themes/ktown/island/natural%20disasters.htm

Comments

Post a Comment