Minnie McGee, Killed her Children with Matchstick Tea

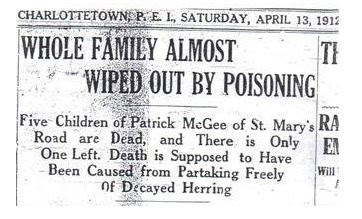

The spring of 1912 on PEI must have been a shocking one.

Minnie's mother died when she was 16. As the oldest sibling, she took on many of her late mother's duties. Five years later, in 1898 she married Patrick McGee. In the 13 years of their marriage, they had nine children - Louis, Penzie, Johnny, George, Bridget, Thomas, Albert, Mary, and Clara.

Albert, unfortunately, died at a young age. I was unable to find the cause or the year.

By this point, the attorney general and law enforcement were suspicious and Johnny was removed from the home and placed with his grandfather. Unfortunately, he died at his grandfather's home a few days later.

When it was reported Minnie was arrested for murder, people were stunned. Minnie had not really been seen outside her home in three years (one theory is that this was due to depression after the deaths of three of her young children) but the nature of the crime surprised many. Others blamed her husband, claiming he was never home and when he was he treated her poorly.

Strangely, during the trial, friends and family questioned her mental state, but the defence didn't pursue a not guilty by reason of insanity plea.

In 1914, the federal Minister of Labour introduced a bill to outlaw the manufacturing, import, and sale of matches made from white phosphorous. If approved (and it was), Canada would join a host of nations who had banned the compound. One of the main reasons it was banned was employees working with the compound were becoming ill with bone disorders and phossy jaw (AKA phosphorous necrosis of the jaw). Phossy jaw was caused by working with white (AKA yellow) phosphorous without the proper safeguards to protect the workers from the vapour of the compound. The vapour would destroy the bones of the jaw. This condition was most commonly found in the 19th and 20th centuries matchstick industry!

When white phosphorous is consumed, the results are the symptoms shown by the McGee children before they died.

Who he is referencing is rather obvious.

The judge sentenced her to hang. She was the first woman on PEI to be sentenced to hang.

Thankfully for Minnie, her community started a petition that she be granted clemency as she was clearly insane and stated that Minnie should be sent to an asylum as she was not "mentally responsible for her deeds." The petition had the support of the local minister, physicians, family, neighbours, and even members from surrounding jurisdictions.

In murder trials, this act of clemency (commuting a sentence), had to be done by the federal Department of Justice. The Minister of Justice commuted the sentence to life imprisonment and she was sent to the Dorchester Penitentiary in New Brunswick.

However, Minnie became "violently insane" within four months of being at the penitentiary and was sent back to PEI and committed to the Falconwood Hospital, a mental asylum.

On 20 February 1913, the now 38 years old Minnie was admitted to the hospital. Her admission record is interesting. Patrick was still listed as her next-of-kin (she would never see him again), and in the area to record the diagnosis, it read "poisoned all her children". As Dr. Sharon Myers states, "It was as if the act itself had become her mental disease, rather than a product of it."

There are few records of her 14 years in Falconwood. But, it is known that Superintendent Dr. Victor Goodwill believed in a moral, therapeutic, and manual labour (but not excessive) approach rather than restraints and heavy medication. However, Falconwood was also dealing with overcrowding. By 1926, Falconwood was overcrowded by 26% - which did affect the effectiveness of treatment and the treatment and respect given to the patients.

In 1927, Dr. Goodwill actually released Minnie. The exact reasons for her release are unknown. Perhaps, he believed she was sane and could be a productive member of society? Or perhaps with the overcrowding at Falconwood, she was one of the patients that were well enough to go back into society?

This did not go well for Minnie. For six months she worked at the PEI Hospital under a false name. When her cover was blown, many were angry at her release and the argument was made that as she was sane enough to be out of Falconwood, she was sane enough to go back to prison for her crimes. As the Dorchester Penitentiary closed its female ward in 1923, she was sent to the federal prison in Kingston instead.

Now 53, she was admitted to the prison with her sister now listed as her next-of-kin. But, like with the Dorchester Penitentiary, she was not there long. The doctors in the prison believed Minnie was still insane and diagnosed her as having manic depression and mania. The federal Minister of Justice ordered Minnie be returned to Falconwood.

When she returned, Falconwood had a new Superintendent, but it was still overcrowded.

On a side note, there is evidence that many of the patients being admitted to Falconwood, were not dealing with mental health issues. For example, there is evidence that two brothers were admitted. One had chest pain and the other just seemed to be there to keep him company. In another case, the Provincial Infirmary was informed they were going to receive two boys and one girl from the Protestant Orphans Home (they were a little overcrowded). When the Infirmary received three boys instead they sent one to the asylum!

By the time Minnie was 70, she was still in the asylum. But, based on records she did have a certain amount of freedom. There are mentions of her wandering off, visiting her sister for two weeks, visiting the families of some Falconwood employees, etc. This means she was given some freedoms during this period (1945-1946).

Minnie died in Falconwood in 1953 at the age of 78.

The story of Minnie McGee demonstrates the hardships of Island life in 1912, the dangers young children faced in the winter (such as getting pneumonia), and the importance of mental health. Minnie lost her three youngest children, was (from known accounts) abused by her husband, left alone to care for the remaining children, and was dealing with depression. Unfortunately, her story does not have a happy ending.

Bellefleur, N. Echoes of McGee tragedy still haunt the Island. The Graphic. April 25, 2012. http://www.peicanada.com/eastern_graphic/news/article_0fc18bbe-19fd-5176-aaa8-45193cb2e773.html

Dr. Myers, S. "The Apocrypha of Minnie McGee: The Murderous Mother and the Multivocal State in 20th-Century Prince Edward Island." Acadiensis [Online], 38.2 (2009). Available at https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/acadiensis/article/view/12733/13663

In 1912, Minnie McGee (born Mary Cassidy) killed six of her children with matchstick tea, something I will explain in a moment. But first, what led to this?

Minnie's mother died when she was 16. As the oldest sibling, she took on many of her late mother's duties. Five years later, in 1898 she married Patrick McGee. In the 13 years of their marriage, they had nine children - Louis, Penzie, Johnny, George, Bridget, Thomas, Albert, Mary, and Clara.

Albert, unfortunately, died at a young age. I was unable to find the cause or the year.

Not long after Albert's death, Mary and Clara, only a toddler and infant at the time, became ill with pneumonia and died in the winter of 1912.

That April, five of the six remaining children fell ill, all with the same symptoms - chest, head, and stomach pain; vomiting; pale skin; bluish lips; and weak pulses. They became too weak to walk and finally, their hearts gave out and all five died on the same day.

Word was sent to their father, Patrick, when they fell ill and he returned home on 20 April 1912. Only to learn that three of his children had already died. The other two died later that evening.

These five children were:

Louis, age 13

Penzie, age 12

Georgie, age 8

Bridget, age 6

Thomas, age 5

Patrick was able to stay for the funerals on Sunday but had to return to work in Nova Scotia on Monday. It appears Patrick was often away for extended periods working, leaving Minnie at home with the children.

Patrick was able to stay for the funerals on Sunday but had to return to work in Nova Scotia on Monday. It appears Patrick was often away for extended periods working, leaving Minnie at home with the children.

At first, it appeared the children consumed bad herring and became ill. Minnie was spared becoming ill because she was larger, and like many poorer families, mothers often gave their children larger portions than themselves. But there were suspicions, and the coroner conducted autopsies on all five children and sent samples to Montreal for analysis.

The last remaining child was Johnny, age 10.

When his siblings fell ill, he was at his uncle's home (Minnie's brother) working. He returned home when his siblings died. He was set to return to his uncle's home two days after the funeral. But, when the uncle arrived, Johnny was ill.

By this point, the attorney general and law enforcement were suspicious and Johnny was removed from the home and placed with his grandfather. Unfortunately, he died at his grandfather's home a few days later.

An autopsy was performed on Johnny and the physicians concluded, without the use of chemical testing, he died from phosphorous poisoning. Their diagnosis was later confirmed by McGill University, who had the proper equipment to test the tissue samples.

When it was reported Minnie was arrested for murder, people were stunned. Minnie had not really been seen outside her home in three years (one theory is that this was due to depression after the deaths of three of her young children) but the nature of the crime surprised many. Others blamed her husband, claiming he was never home and when he was he treated her poorly.

In the summer session of the PEI Supreme Court, Minnie was tried for the murder of Johnny. The jury deliberated for only a half-hour and of three possible verdicts presented by the judge (guilty, not guilty, and not guilty by reason of insanity), the jury declared Minnie guilty, but strongly recommended mercy.

Strangely, during the trial, friends and family questioned her mental state, but the defence didn't pursue a not guilty by reason of insanity plea.

In Minnie's signed confession, she admitted she soaked matches in weak tea and sugar water and fed it to her children a few days before they died with the meal of herring. While she believed she only fed this poisonous tea to them once, she could not be certain.

Minnie told Constable McKearney that the idea of killing her children was haunting her day and night and she believed her children would be better off in heaven. She also admitted to planning to consume the poisonous tea herself.

Minnie told Constable McKearney that the idea of killing her children was haunting her day and night and she believed her children would be better off in heaven. She also admitted to planning to consume the poisonous tea herself.

Now, some of you may be wondering how this would be poisonous enough to kill children so quickly unless they were fed a lot of it. Well, white phosphorous can be very poisonous.

|

| As you can see, the match heads a colourful and you can clearly see the white and red phosphorous. (Image Credit: Dr. Kevin A. Boudreaux) |

In 1914, the federal Minister of Labour introduced a bill to outlaw the manufacturing, import, and sale of matches made from white phosphorous. If approved (and it was), Canada would join a host of nations who had banned the compound. One of the main reasons it was banned was employees working with the compound were becoming ill with bone disorders and phossy jaw (AKA phosphorous necrosis of the jaw). Phossy jaw was caused by working with white (AKA yellow) phosphorous without the proper safeguards to protect the workers from the vapour of the compound. The vapour would destroy the bones of the jaw. This condition was most commonly found in the 19th and 20th centuries matchstick industry!

|

| Phossy Jaw. Looks painful. (Image Credit: Phossy Jaw) |

When white phosphorous is consumed, the results are the symptoms shown by the McGee children before they died.

Another reason the matches were banned was the match heads were brightly coloured and looked like candy, as a result, some children would find them and suck on them, thinking they were candy. The Minister also brought up how easily they could be used to poison others as the matches were,

"a convient and inexpensive means of criminal poisoning, and were employed in this way by a brutal parent in Prince Edward Island a little over a year ago for the destruction of her entire family."

Who he is referencing is rather obvious.

After her conviction, in a detailed confession, she admitted to giving her five other children matchstick tea. She also confessed to serving it to Johnny when he returned home for his sibling's funerals. But, she also stated that she had bought more matches, intending to serve herself the same lethal tea.

At her sentencing, she asked the judge to take mercy on her,

At her sentencing, she asked the judge to take mercy on her,

"I have had a hard life. In January my head went all astray and worse in February and worse in April. Pain in my head right through away in there. . . . This last four months, pain was dreadful. I was going to do away with my own life; I cannot do away with the pain I have in my head."She also accused Patrick of beating her, not helping her when she was ill, and claimed he did not protect the children,

"He had four months of warning...It was his fault not mine. It was all his fault - I dearly loved the children."Based on this statement, she must have believed that her husband should have seen that she was not herself after they lost their three youngest children and should have acted to protect the children.

The judge sentenced her to hang. She was the first woman on PEI to be sentenced to hang.

Thankfully for Minnie, her community started a petition that she be granted clemency as she was clearly insane and stated that Minnie should be sent to an asylum as she was not "mentally responsible for her deeds." The petition had the support of the local minister, physicians, family, neighbours, and even members from surrounding jurisdictions.

In murder trials, this act of clemency (commuting a sentence), had to be done by the federal Department of Justice. The Minister of Justice commuted the sentence to life imprisonment and she was sent to the Dorchester Penitentiary in New Brunswick.

However, Minnie became "violently insane" within four months of being at the penitentiary and was sent back to PEI and committed to the Falconwood Hospital, a mental asylum.

On 20 February 1913, the now 38 years old Minnie was admitted to the hospital. Her admission record is interesting. Patrick was still listed as her next-of-kin (she would never see him again), and in the area to record the diagnosis, it read "poisoned all her children". As Dr. Sharon Myers states, "It was as if the act itself had become her mental disease, rather than a product of it."

There are few records of her 14 years in Falconwood. But, it is known that Superintendent Dr. Victor Goodwill believed in a moral, therapeutic, and manual labour (but not excessive) approach rather than restraints and heavy medication. However, Falconwood was also dealing with overcrowding. By 1926, Falconwood was overcrowded by 26% - which did affect the effectiveness of treatment and the treatment and respect given to the patients.

In 1927, Dr. Goodwill actually released Minnie. The exact reasons for her release are unknown. Perhaps, he believed she was sane and could be a productive member of society? Or perhaps with the overcrowding at Falconwood, she was one of the patients that were well enough to go back into society?

This did not go well for Minnie. For six months she worked at the PEI Hospital under a false name. When her cover was blown, many were angry at her release and the argument was made that as she was sane enough to be out of Falconwood, she was sane enough to go back to prison for her crimes. As the Dorchester Penitentiary closed its female ward in 1923, she was sent to the federal prison in Kingston instead.

Now 53, she was admitted to the prison with her sister now listed as her next-of-kin. But, like with the Dorchester Penitentiary, she was not there long. The doctors in the prison believed Minnie was still insane and diagnosed her as having manic depression and mania. The federal Minister of Justice ordered Minnie be returned to Falconwood.

|

| Minnie McGee later in life. (Image Credit, UPEI) |

When she returned, Falconwood had a new Superintendent, but it was still overcrowded.

On a side note, there is evidence that many of the patients being admitted to Falconwood, were not dealing with mental health issues. For example, there is evidence that two brothers were admitted. One had chest pain and the other just seemed to be there to keep him company. In another case, the Provincial Infirmary was informed they were going to receive two boys and one girl from the Protestant Orphans Home (they were a little overcrowded). When the Infirmary received three boys instead they sent one to the asylum!

By the time Minnie was 70, she was still in the asylum. But, based on records she did have a certain amount of freedom. There are mentions of her wandering off, visiting her sister for two weeks, visiting the families of some Falconwood employees, etc. This means she was given some freedoms during this period (1945-1946).

Minnie died in Falconwood in 1953 at the age of 78.

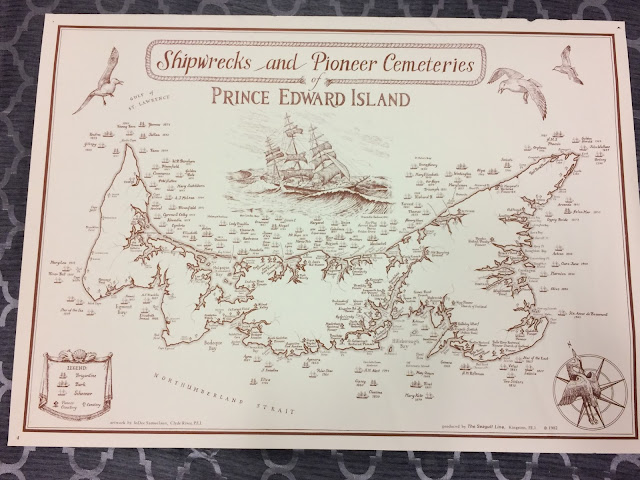

The story of Minnie McGee demonstrates the hardships of Island life in 1912, the dangers young children faced in the winter (such as getting pneumonia), and the importance of mental health. Minnie lost her three youngest children, was (from known accounts) abused by her husband, left alone to care for the remaining children, and was dealing with depression. Unfortunately, her story does not have a happy ending.

Bellefleur, N. Echoes of McGee tragedy still haunt the Island. The Graphic. April 25, 2012. http://www.peicanada.com/eastern_graphic/news/article_0fc18bbe-19fd-5176-aaa8-45193cb2e773.html

Dr. Myers, S. "The Apocrypha of Minnie McGee: The Murderous Mother and the Multivocal State in 20th-Century Prince Edward Island." Acadiensis [Online], 38.2 (2009). Available at https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/acadiensis/article/view/12733/13663

McGuigan, J.C. The Tragedy of Minnie McGee. 2014.

Comments

Post a Comment